SUNAGA Emiko

Nowadays, libraries around the world are actively working on digital publishing of their holdings. Previously, to obtain just several dozens of copied pages of necessary materials, one had to travel abroad and undergo troublesome procedures to receive copying permission from each library, but now rare items from any period and from any country have become available for viewing from home. At the same time, a new problem has arisen: how can we effectively use the overflowing amount of digital materials that cannot be even read in a lifetime?

Also, reading through an old book or handwritten document in an unaccustomed foreign language takes time and requires knowledge of the corresponding language. There, the OCR (Optical Character Recognition) technology can tremendously enhance readability by converting regions of digital images that contain characters into a machine-readable text format. The OCR technology has already taken root as a comfortable function in our everyday lives, with the Google Lens feature allowing to read characters by just pointing the smartphone’s camera or LINE’s OCR feature extracting characters from messaged photos to text, etc.

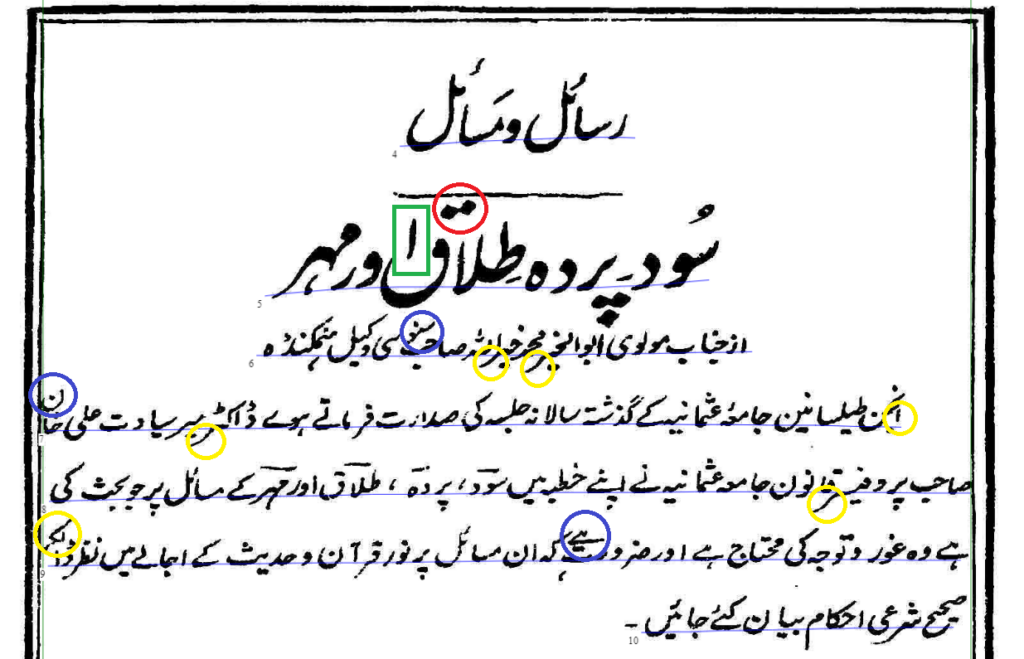

The OCR technology has developed in the domains of the Latin alphabet and Chinese characters. On the other hand, OCR of the Arabic characters used in such languages as Arabic or Persian is still underdeveloped. Accurate recognition of the Arabic characters is difficult due to frequent use of curves, joining of adjacent letters within a word, several letters being differentiated by the number of small points, etc. In the South Asian language of Urdu that uses the Arabic script, in some cases letters in the center or ending of a separate word are written over or below the baseline which makes it difficult to analyze the layout. For example, in the picture below, the point marked with the red circle and the character marked with the green square intrudes the previous word, while the part marked with the yellow circle intrudes the following word. The part marked with the blue circle appears mounted on the previous word to squeeze the inter-character space. Machines cannot recognize such layout-related specifics (thin lines drawn under each text line represent the machine-recognized layout in Transkribus mentioned below).

Machine-recognized page from a journal in Urdu published in 1935

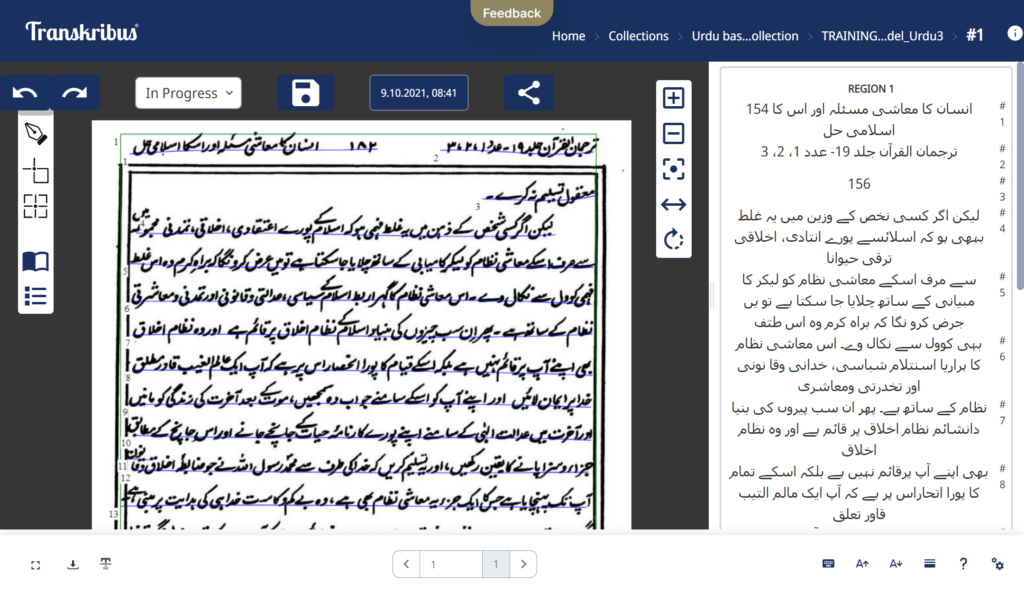

As for the handwritten characters, because of the distorted forms and big differences in individual writing styles, in many cases, even such commercial OCR software as ABBYY FineReader PDF or Yomitori Kakumei cannot correctly recognize the text. Therefore, with the purpose to enhance machine-reading of such handwritten characters, joint research has been in progress in the field of HTR (Handwritten Text Recognition). For example, the open-source research infrastructure project of Transkribus, in which the University of Innsbruck plays a pivotal role, is putting considerable effort into machine learning of various characters applying AI technology. Machine learning of the Arabic characters of specific handwriting styles that vary depending on the language and time period is also underway, employing a participation–type platform for researchers.

Operation screen of Transkribus during machine-learning of an item in Urdu (https://readcoop.eu/transkribus/)

OCR and HTR technologies have already been introduced in practice at libraries and archives. For example, the ”Next Digital Library”, a service the National Diet Library of Japan launched in 2019, by applying image recognition and text recognition (OCR) to illustrations and full text, enables searching by images and key words, which makes it possible to locate an art catalog containing a certain painting, or pick up a toponym or a personal name that appears only once in the main text.

Next Digital Library of National Diet Library (https://lab.ndl.go.jp/dl/)

This service is very convenient, enabling the simultaneous search though all books housed in the National Diet library (but, of course, this is limited to the materials that have been digitalized). For instance, when conducting research on religious rites in Islam, previously, you would make guesses and look through various religion–related books, publications on history, geographical descriptions, travel reports, etc., but now you can probably simply find what you are looking for in a description of celebration dishes eaten during or after religious rites in a recipe book. Even if the word “Qur’an” is not registered as a key word or in the contents, should it appear in the main text even once, you can easily locate it there. This will likely lead to unexpected encounters with not-yet-seen materials more than ever before.

Furthermore, in 2022, a new function that displays OCR-recognized text over digital images of classic books and materials was added. OCR and HTR technologies have been evolving rapidly, already becoming indispensable for effective use of digitalized materials.

*This is an English translation of a Japanese article from the “Catalog of the University of Tokyo Asian Research Library DigitalCollections 2017-2023” published on February 29, 2024.

For more information about the catalog, please click here.

March 26, 2024