U-PARL has published its 2022 leaflet.

The background of the leaflet uses images from the Asian Research Library Digital Collections of the University of Tokyo. U-PARL’s Project Research Fellow Michiko NAKAO and Project Specialist Yuto NAKAI will provide explanations for these materials.

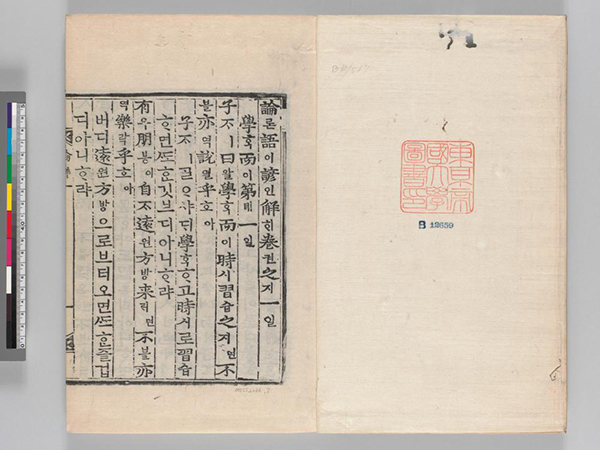

Commentary on the “Ŏnhaebon 諺解本 언해본”

In Japan, Hangul is now seen everywhere. The Hangul writing system was promulgated in 1446 under the name Hunmin chŏngŭm / 訓民正音/ 훈민정음 by King Sejong, the fourth king of the Joseon Dynasty. Hunmin chŏngŭm was created as an alphabet that could be used by the people. The name “Hangul” was not used until the beginning of the 20th century.

Before the creation of Hangul, the Korean people had only Chinese characters as a means of expressing their language, and even when writing their native language, they used phonetic loanwords in Chinese characters. The formation of Hunmin chŏngŭm was also written first in Chinese characters. Later, Hunmin chŏngŭm Ŏnhaebon / 訓民正音 諺解本 /훈민정음 언해본 was compiled and written in Hangul. The term “Ŏnhae / 諺解 / 언해”, literary meaning local speech, refers to an explanation of a classical Chinese text in the vernacular Korean script.

Japanese scholar Shimpei OGURA (1882-1944), who studied the Korean language at Gyeongseong Imperial University and Tokyo Imperial University, wrote: “In Korea, there are commentaries with a special style, such as Nonŏ Ŏnhae 論語諺解 논어 언해 (Vernacular Exegesis of the Analects) and Pak T’ongsa Ŏnhae 朴通事諺解 (Vernacular Exegesis by Interpreter Pak), etc., which are called Ŏnhae / 諺解 or 諺釈 (humble interpretation). These are mainly interpretations of the meanings of Chinese texts in the Korean language.

Originally, the word “Ŏn 諺” was a term used to belittle one’s own country compared to Chinese civilization. For example, the Hangul is called Ŏnhae 諺解 (humble interpretation), the Korean language is called 諺語 or 国諺 (humble language), and the phonetic transcriptions in the Hangul are called 諺吐 (humble transcription).

There are many examples of the use of Hangul to explain words and phrases in Japanese, Manchu, and Mongolian dictionaries and textbooks, but these are never called Ŏnhae. In other words, the term Ŏnhae is used only for the Chinese language. This is evidence of how much the Koreans worship Chinese civilization.”

It was not until the 16th century that the term “Ŏnhae” came to be used as part of the title of a book, and at the end of the 16th century, the Proofreading Office (校正庁 Kyojŏng-ch’ŏng) was established by order of King Sŏn-jo, the 14th King of the Joseon Dynasty, to proofread the classical books and other documents. This agency began to publish books on the analysis of proverbs in Confucian scriptures, such as the Sohak Ŏnhae 小学諺解 and the Nonŏ Ŏnhae 論語諺解.

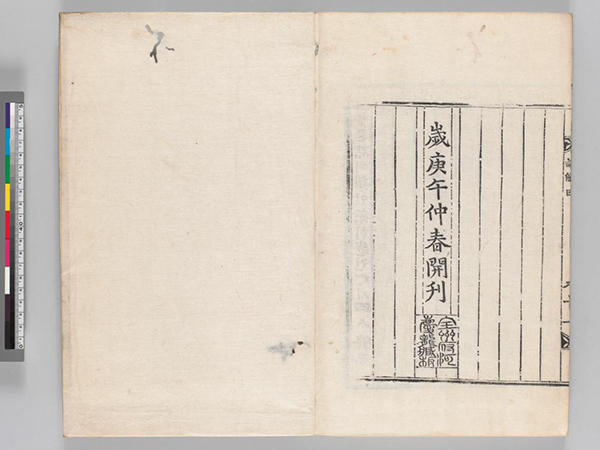

The cover of the 2022 U-PARL leaflet is based on the design of Nonŏ Ŏnhae in the possession of the University of Tokyo General Library. Nonŏ Ŏnhae was published privately in 1810 or 1870 and bears the seal “全州 河慶龍蔵板 Chŏnju Ha Kyŏng-nyong jangp’an” as the place of publication. U-PARL digitized all four volumes of Nonŏ Ŏnhae in 2018, and all images are now available in the Asian Research Library Digital Collections of University of Tokyo.

|

|

Michiko NAKAO, U-PARL

【References】

小倉進平著・河野六郎補注『朝鮮語学史』刀江書院、1964年

http://opac.dl.itc.u-tokyo.ac.jp/opac/opac_link/bibid/2000645853

Hyeonju Ahn, A Study on Printed Books of Unhaebon “The Sayings of Confucius (論語)” in Chosun Dynasty, Journal of the Institute of Bibliography, no. 26, 2003

安賢珠「조선시대에 간행된 諺解本《論語》의 板本에 관한 考察」『書誌學硏究』26、2003年

福井玲『韓国語音韻史の探究』三省堂、2013年

http://opac.dl.itc.u-tokyo.ac.jp/opac/opac_link/bibid/2003103069

野間秀樹「ハングルという文字体系を見る―言語と文字の原理論から―」野間秀樹編著『韓国語教育論講座3』くろしお出版、2018年

http://opac.dl.itc.u-tokyo.ac.jp/opac/opac_link/bibid/2003433061

Commentary on the Manchu version of Baqi manzhou shizu tongpu 八旗満洲氏族通譜

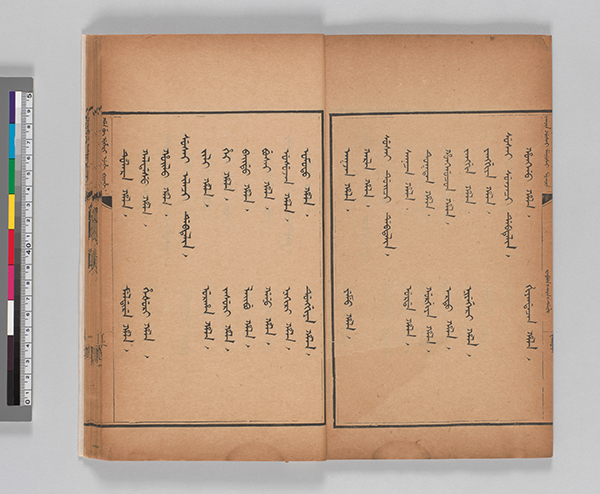

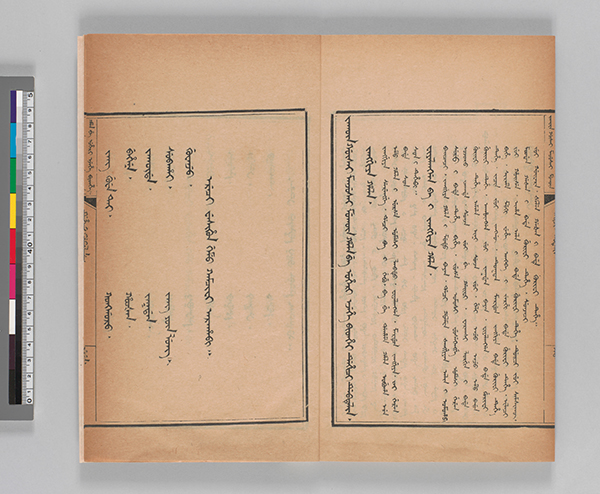

Baqi manzhou shizu tongpu 八旗満洲氏族通譜, jakūn gūsai manjusai mukūn hala be uheri ejehe bithe in Manchu, is a genealogical document compiled by imperial order of the emperor of the Qing dynasty in the 18th century, and the cover of this leaflet features the Manchu version of this document.

The Qing dynasty, daicing gurun 大清国, was founded by the Manju people who lived in the forested areas of Manchuria, present-day northeastern China, and the Russian coastal region, in the 17th century. Although the Manju people settled in houses and made farming their main occupation, their society and culture had more in common with those of nomadic groups in Central Eurasia such as the Mongols rather than those of China. They were skilled at horseback archery, had characteristic hairstyles called bianfa 辮髪, and spoke Manchu, a Tungusic language. “Manju” is an autonym for their nation or group, and “Manchu” 満洲 is its phonetic transcription in Chinese characters.

While Hideyoshi TOYOTOMI 豊臣秀吉 and Ieyasu TOKUGAWA 徳川家康 were establishing their governments in Japan, a hero called Nurhaci appeared in Manju society and conquered various clans and groups, which had been divided with their own territories, and established a nation called Manju gurun, which became the foundation of the Qing dynasty. At that time, the Manchu script was created based on the Mongolian script by order of Nurhaci to smoothly run the nation by administrative documents. Manchu script was written vertically and read from left to right. A Manchu letter represents a vowel or consonant, and each letter changes its form at the beginning, middle, and end of the word. Manchu script is an alphabet derived from the Aramaic and Sogdian scripts.

(photo by the author)

Nurhaci divided the Manju people who had submitted to his nation into eight gūsa 旗 groups (or army corps) and ruled them. This was called jakūn gūsa 八旗 and those who were incorporated into each gūsa were called Qiren 旗人. The Qing dynasty conquered China, Mongolia, and Central Asia with the military force of jakūn gūsa and became a great empire that exerted its influence over the eastern part of Eurasia. Baqi manzhou shizu tongpu is a document that categorizes Qiren of Manju who belonged to jakūn gūsa from the foundation of the nation in the 17th century to the beginning of the 18th century by clan and lineage, and comprehensively lists their origins, genealogies, and government posts. In the parts used on the cover of the leaflet, the names of the clans and people, their achievements, affiliations to gūsa groups, and names of government posts are described. This document was compiled by Hongzhou 弘昼, the fifth son of the Yongzheng emperor 雍正帝, and others under the order of the Yongzheng emperor and completed at the end of the ninth year of Qianglong 乾隆 (1745). In the present study of the Qing dynasty, this is an essential document for searching persons, restoring genealogy, and elucidating the system of jakūn gūsa.

Baqi manzhou shizu tongpu vol. 40

There are two versions of Baqi manzhou shizu tongpu, one is in Manchu and the other in Chinese, and the facsimile edition of the Chinese version has already been published in China. On the other hand, the facsimile edition of the Manchu version has not yet been published, and the institutions holding it are limited, so it has been extremely difficult for the general public to access this document. In this situation, U-PARL noticed that the Manchu version of Baqi manzhou shizu tongpu (32 volumes, 81 books in total) is kept in the University of Tokyo library system, and published the image data of the entire volume in 2018.

The publication of the Manchu version of Baqi manzhou shizu tongpu by U-PARL became a big topic among researchers specializing in Manju and the Qing dynasty. It is used in the cover design of the leaflet as a representative example of U-PARL’s contribution to Asian studies.

Yuto NAKAI, U-PARL

*The original of the Manchu version of Baqi manzhou shizu tongpu is not yet registered with the OPAC (as of 2022 May).

July 21, 2022